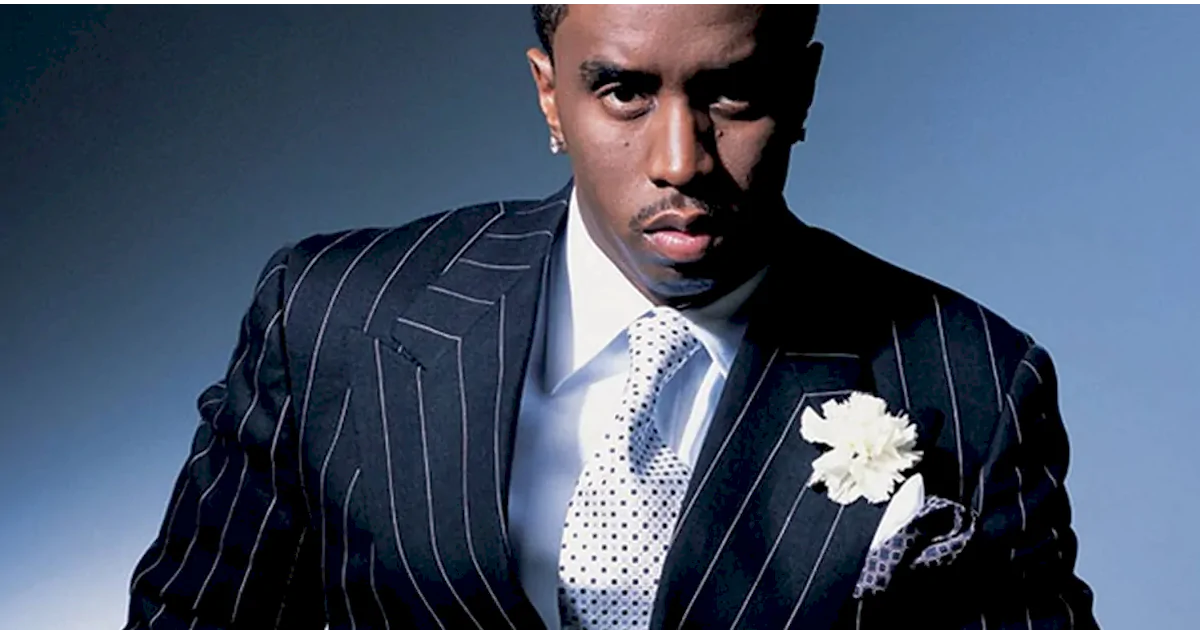

Puff Daddy and the Player Hater Syndrome

[Esses dias a Marie apareceu com esse tuite sobre o brasileiro e o medo do “invejoso”. Lembrei imediatamente desta resenha/ ensaio aqui, publicada em pt-br na coletânea Beijar o Céu, de 2006, dentro da coleção “iê-iê-iê” da Conrad Editora. O nome em português ficou “Puff Daddy e a Síndrome do Invejoso”. Outra hora eu pego para escanear. Se quiser o livro competo (vale muito , especialmente o prefácio, que só existe nessa edição) vale comprar no Estante Virtual. Abaixo eu coloquei a versão em ingulês, que tá no livro Bring The Noise, e inclusive conta com um bom adendo no final, que não existe na versão em pt-br, sobre hip hop estadunidense e capitalismo, quem sabe no futuro eu adiciono em português também. O livro original, muito bom mesmo, pode ser encontrado na biblioteca russa (foi de onde eu tirei). Boa leitura e valeu Simão Reinaldo!]

By Simon Reynolds

A couple of songs into Puff Daddy’s new album Forever there’s a comic interlude, a skit about people phoning the ‘Player-Haters Anonymous Hotline’. One caller confesses that he’s fallen off the wagon and has been ‘hatin’ today . . . all week as a matter of fact’. Another, distraught and at the end of his tether, warns the hotline counsellor that he’s got a key in his hand and is on the verge of scratching ‘this motherfucker’s Bentley’.

The rapper CJ Mac’s new album Platinum Game features the comedy interlude ‘Hating Game’, a spoof on the television show ‘The Dating Game’ in which each contestant is asked how he would react if he discovered his woman in flagrante delicto with CJ Mac. And on her debut album Ruff Ryders’ First Lady, Eve, goes one step further with the parody track ‘My Enemies’, in which she mocks the trend of songs about players and player-haters itself.

The ‘player’, a sort of dandy megalomaniac, and the ‘player-hater’, the non-entity who resents the player’s ostentatiously opulent lifestyle, are twinned concepts that have dominated the imagination of mainstream rap for the last few years. The player persona was originally codified and popularized by The Notorious B.I.G. – real name Christopher Wallace – the rap star who was murdered in a drive-by shooting in 1997 and who is the main cash-cow of Puff Daddy’s label, Bad Boy Entertainment. Player signifies a top dog, the big shot who calls the shots. But it also evokes the idea of a playboy, someone who visibly basks in the wealth and prestige of being a winner. Where that earlier archetype of rap masculinity, the gangsta, focused on the means of wealth production (crime) and all its drawbacks (paranoia, the constant possibility of death), player-oriented rap emphasizes the leisure and pleasure aspects of the lifestyle: the fine women, the conspicuous consumption of luxury goods, the clique-ishness of associates and hangers-on. The realities of where the ‘paper’ – slang for money – comes from are deliberately kept hazy; the player might be a hustler, a wheelerdealer businessman or an entertainer, it doesn’t really matter.

What does count is being seen to be living large, which is what The Notorious B.I.G. communicated so successfully in the videos for the hit singles from his 1994 debut album Ready to Die. In the videos for hits like ‘One More Chance’ and ‘Juicy’, The Notorious B.I.G. is the epicentre of a Hugh Hefneresque milieu in which champagne is sipped like soda and white accountants discreetly handle B.I.G.’s business affairs leaving him free to . . . play. Into this Eden of languid luxury crept trouble, though, in the snake-like form of the player-hater. In hip hop parlance, to ‘hate on’ somebody is to resent, envy, badmouth and scheme against. Following the initial massive success of The Notorious B.I.G., subsequent Bad Boy releases increasingly conjured a vision of player-haters as a swarming mass of green-eyed small fry.

Notorious B.I.G.’s second album, 1997’s Life After Death, acknowledged this one drawback to the player lifestyle with songs like ‘Mo Money Mo Problems’ and ‘Playa Hater’, while Puff Daddy’s debut No Way Out featured ‘Been Around the World’, with its boastful chorus ‘been around the world / and I been player-hated’. On Harlem World, the debut by Ma$e (Bad Boy’s Notorious B.I.G. surrogate), player-haters became a dominant lyrical topic with songs and skits like ‘Lookin’ at Me’, ‘Wanna Hurt Ma$e?’, ‘Hater’ and ‘Niggaz Wanna Act’. The closing ‘Jealous Guy’ sees Ma$e hoarsely crooning a rule from his ‘New Pimp Testament’ – ‘you can’t be a player, and hate the players – that don’t make no sense’, which translates as only losers feel bitter towards winners.

Although Bad Boy’s commercial success and influence on hip hop peaked at the end of 1997, the player-hater concept coined by the label has continued to proliferate through the rap scene like a virus. Examples from this year include Nas’s ‘Hate Me Now’, Big Hutch’s ‘Player Hater’, B.G.’s ‘Don’t Hate Me’ and Tear Da Club Thugs’ ‘Why Ya Hatin’?’ as well as albums like Willie D’s Loved By Few, Hated By Many. The Beatnuts’ current hit ‘Watch Out Now’ jeers ‘you wanna hate me / cause your wife wants an autograph / from the look in her eyes I can see she wants more than that’. According to the player’s twisted logic, stealing other men’s women is just what players do. It’s the cuckold who is being perverse by begrudging the player for doing what comes naturally, what the cuckold would do if he was in the player’s shoes.

Player-hating is bizarrely similar to Nietzsche’s concept of ressentiment: the hostility of the oppressed towards their superiors. He diagnosed and denigrated those feelings as mere self-defeating rancour and impotent rage. The difference is that the hip hop player is a self-made aristocrat, a former member of the underclass who’s raised himself from its ranks and seized his chance to ‘shine’. The ressentiment of those you have left behind is an integral element of the player fantasy. Indeed a retinue of haters is an essential accoutrement of success, just another status symbol alongside the Versace furs, platinum Rolexes, Mercedes Benzes, diamond-encrusted jewellery and endlessly flowing Cristal and Hennessy. Because Puff Daddy represents himself as the ultimate player, a sort of hip hop Donald Trump and ‘black Sinatra’ rolled into one, it figures that he’s got to have the most haters. Moving well beyond the lighthearted jibes at player-haters on his debut album, Forever presents a beleaguered Puffy, bewildered and wounded by the resentment stirred up by his relentless rubbing of his success in the world’s face.

On the album’s bombastic intro track, he declaims: ‘I will look in triumph at those who hate me . . . Though hostile nations surround me, I destroy them all in the name of Lord.’ This mogul-as-martyr shtick climaxes with a direct quote from Jesus as he’s being crucified: ‘Lord forgive them, for they know not what they do.’ It’s not the only time on Forever that Puffy compares himself to Christ; one song includes the line ‘I’m on the run like Jesus’. What’s striking about these messianic allusions is that earlier this year Combs got into serious trouble in a dispute that involved a similar self-identification with Jesus Christ. As a guest-rapper on Nas’s player-hater-themed single ‘Hate Me Now’, he consented to be filmed for scenes in the video of the two rappers being crucified. Regretting this decision, he asked Nas’s manager Steve Stoute to remove the crucifixion imagery before it was aired. When the video was shown on television unchanged, an enraged Puff Daddy and two of his minions visited Mr Stoute in his office on 15 April, and roughed him up. Although no charges were pressed by the victim and accounts of the incident conflict, the Manhattan District Attorney’s office is still considering prosecution.

If he doesn’t actually believe he’s Christ, Puff Daddy reckons he’s pretty tight with him – judging by ‘Best Friend’, a bizarre and saccharine serenade to Jesus that samples Christopher Cross’s sentimental soft rock ballad ‘Sailing’ and uses the gospel backing vocals of the Love Fellowship Choir. It’s one of Forever’s few glints of joy. Unlike Bad Boy’s earlier pleasure-centred albums, Forever makes the player’s life seem like a trudge through a vale of blood, sweat, and tears. What exactly does a twenty-nine-year-old tycoon with an East Hampton mansion and a many-tentacled business empire (including record, management and publishing companies, restaurants, the magazine Notorious and the Sean John clothing line) have to complain about? Mostly, it’s those pesky player-haters. When Puff Daddy’s not boasting, he’s bleating: in ‘What You Want’, about hangers-on who hang out with him only for the reflected glory, about ‘bitches, hands out, grabbing / niggers, hating, scheming, and backstabbing’. In the catchy ‘Do You Like It . . . Do You Want It’, Puff Daddy discovers a new woe of the over-achiever: the ennui of those whose triumphs come so thick and fast that victory is no longer a thrill. ‘Where do you go from here when you’ve felt you’ve done it all / When what used to get you high don’t get you high no more?. . . When you expected to win, they ain’t surprised no more?’

As the album proceeds, Puffy’s paranoia escalates. In ‘Is This the End’, he describes himself as an enemy of the state over a backing track that sounds as frantic as a panic attack, while ‘Reverse’ dramatizes a defiant Puffy as ‘me against a million, billion of y’all motherfuckers’. Finally, his persecution complex flowers with the closing track ‘PE 2000’, a remake of Public Enemy’s 1987 classic ‘Public Enemy No. 1’. With a video that depicts the rapper pursued by a sinister black helicopter, and lyrics that beseech ‘let me ask you what you got against me? / Is it my girl or is it the Bentley?’, the song replaces Public Enemy’s political militancy with Puffy’s trademark blend of self-aggrandizement and self-pity. The original song was the opening salvo and statement of intent in a career that revolutionized hip hop; although they were just starting their career, Public Enemy’s paranoia-in-advance was justified, as their controversial opinions were set to make them lightning rods. Posing as a homage, ‘PE 2000’ might really be an exorcism of Public Enemy’s spirit, at a time when the group’s political consciousness has been almost totally marginalized from mainstream rap culture. And the hubris of covering the song invites unflattering comparisons: not just between Puff Daddy’s weak rapping and self-pity and Chuck D’s authoritative cadences and charismatic gravitas, but between the imaginative poverty of the Bad Boy worldview and the Public Enemy vision. Thanks to Bad Boy, but also more gangsta-aligned labels like No Limit and Cash Money, mainstream hip hop has reverted to its pre-1987 days when rapping largely comprised ‘talking on myself’ (i.e. boasting) and rappers sported gold chains. Jay-Z’s current single ‘Girl’s Best Friend’, for instance, is a love song to diamonds.

Where ‘Public Enemy No. 1’ spoke for the man in the street, ‘PE 2000’ invites the rap fan to identify with the man cruising in the Silver Bentley, brooding over the astonishing fact that money and power does not bring peace of mind.

Transforming the eternal war of the players and the player-haters into a monument of kitsch paranoia, Forever ought to sound the death knell for the player ethos. But rap fans continue to find vicarious enjoyment in the player fantasy, where being hated is the inevitable price for being one of the few who make it in a system that otherwise guarantees anonymity and poverty for most. This is the fantasy structure of rap in the late nineties, where the top hip hop radio station Hot 97 advertises its own Player’s Ball multi-artists concert in between commercials for tele-cash loans by phone (‘to help you through tough times . . . payday comes today’), two-for-a-dollar cheeseburgers and anti-heroin ads. In ‘Diddy Speaks!’, a mawkish, mumbled interlude on Forever, Puff anatomizes the mechanism of this fantasy-identification process; he explains that his full-throttle quest for success wasn’t just selfish, that he was ‘doin’ it for all of us’. It’s as if he’s saying that what really hurts is the ingratitude of the player-haters who have forgotten that he is their representative and stand-in.

Director’s cut of piece published in the New York Times,

10 October 1999

A meme circulated in hip hop from the late nineties onwards: ‘don’t hate the player, hate the game’. It’s appeared as a lyric in countless rap tunes and as a maxim in innumerable interviews. (See also the related concept, ‘game’: if you’ve ‘got game’ it means you’re endowed with mojo, moxie, chutzpah, the seducer’s gift of the gab.) ‘Hate the game’: it’s a tiny chink of enlightenment in the wall of false consciousness, just a hair’s breadth from saying ‘this isn’t personal, our conflict is structural, based in systemic and radically dysfunctional unfairness: a competition in which winners are over-rewarded out of all proportion and everybody else is a loser’. And maybe two hairs’ breadth from saying, ‘let’s change the rules’. Except for the (self) confidence trick that keeps on being pulled: everybody believes, deep down, they can play and win. That ideological sleight is why rap is as American as apple pie and capitalist to the core. It was almost inevitable that a rapper would come along called The Game. And when he arrived, a protégé of Dr Dre and 50 Cent, his stardom inevitable . . . it just seemed to seal finally the fact that rap as ‘black folks’ CNN’ (Chuck D) and a movement of emancipation had long been displaced by rap as entertainment industry and as a career structure for self-advancement on the individual rather than collective level. The Game’s lyrics were self-reflexively about his career trajectory, his moves. He even caught the collective – – > individual shift with his song ‘Dreams’, which equated the civil rights movement with his own ‘war to be a rap legend’: ‘Martin Luther King had a DREAM / Aaliyah had a DREAM . . . So I reached out to Kanye and I brought you all my dreams.’ Still, we should thank him really, because for once it was possible to hate the player and the Game.